2.3 An Introduction to WatershedsEverything in the natural world is connected to other parts. Changes made to one element of a system affect many other elements and/or process throughout the system. A watershed—an area of land that contributes runoff to a lake, river, stream, estuary or bay—is a complex and dynamic natural system. Changes to land cover in upland regions of a watershed affect downstream hydrology; waste inputs from one community can affect water quality further downstream. Impacts to an aquifer, such as water withdrawal, may ultimately affect the flow and health of a nearby stream. The various resources that interact within a watershed—the land, the surface and ground water, the air and the organisms within the watershed—cannot be considered in isolation. By recognizing the interconnections between the components of a watershed and by integrating this understanding into planning and decision making within and across watershed boundaries, negative human impacts on watershed health are more likely to be more effectively managed.

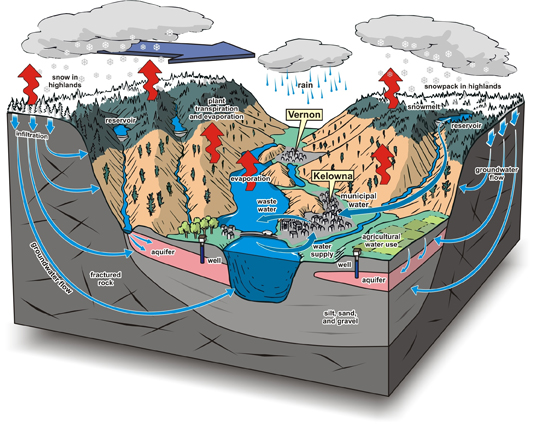

Figure 1 – The Components of a Watershed5 Understanding the hydrologic cycle is critical to understanding how a watershed functions. While both salt water and freshwater are essential parts of the water cycle, the freshwater that we use on a daily basis for drinking water, irrigation, and other uses comprises only 1% of all water on Earth. This small proportion of water is “recycled” through the hydrologic cycle, year after year, through oceans, rivers, rain and the atmosphere (Figure 1). When water falls to the earth as either rain or snow, it either:

The rate of infiltration within a watershed is determined by many factors, including soil permeability, rate of precipitation and the amount and type of vegetation cover on the land surface. Human activity can alter the rate of infiltration by changing the surface of the land. When rain falls or snow melts too fast to allow for infiltration, or when the ground is too hard (impermeable) for infiltration to occur, such as in an urban environment, the water flows over the land as surface runoff (also called overland flow). Surface runoff is evident within a watershed as streams, rivers, lakes, ponds, wetlands and drainage ditches. Water that infiltrates into the ground can take one of several routes:

The areas where precipitation or surface water infiltrates the soil and enters the groundwater system are known as recharge areas. They are often in upland areas of a watershed but may also be in low-lying valleys and floodplain areas. As water evaporates from collecting water bodies, it is returned to the atmosphere, and the cycle repeats itself. No new water is produced: the water that we use today is the same water that existed billions of years ago. How we develop and manage the land within our watersheds ultimately affects the quality of the water that is available for use. In the same way that streams and rivers flow through a collecting basin, the impacts of human activities also flow through a watershed. It should be acknowledged that there are many different scales of watersheds. The scale of watershed that is appropriate to effectively plan for, and manage, a given issue (or issues) will depend on the nature and scope of those issues and the purpose and scope of the planning process. Back to top READ MORE ABOUT: PLANNING FOR WATER AND WATERSHEDS |

|